Affordability of a Liveable Jobseeker Payment is a Non-Issue

Share

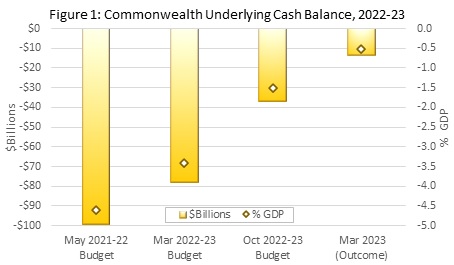

Commonwealth on Track for Diminutive Deficit or Surplus in 2022-2023

In the lead-up to its 2023-24 budget, the Labor Government finds itself in an awkward position, accepting that the Jobseeker payment is “seriously inadequate” and an impediment to regaining work, yet professing that it lacks the financial capacity to afford a meaningful increase anytime soon.

The Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee’s (EIAC) April 2023 Interim Report recommended raising Jobseeker from 70% of the Pension up to 90%. The current Jobseeker base rate for a single person with no children is $693.10 per fortnight. Lifting it up to 90% of the current Pension payment of $971.50 per fortnight would provide the unemployed with an extra $181.25 per fortnight (or $12.25 per day).

Labor has baulked at the cost of the EIAC’s Jobseeker proposal. There is speculation that the upcoming budget will include a $50 per fortnight increase in the Jobseeker payment for those over 55 years of age. It is unclear if that increase will apply to everyone over 55 years of age, or just to the 55 to 59 year old cohort who are currently ineligible for the additional $52 per fortnight already available to those over 60 and who have been unemployed for longer than nine months.

A $3.57 per day rise in the Jobseeker payment for those over 55 years of age (or between 55 and 59) seems rather stingy. One might expect that the plight of the unemployed—among the least well-off and most financially-constrained members of society—would be a high priority in the middle of a cost-of-living crisis.

Before last year’s election, the Labor party abandoned a previous pledge to raise Jobseeker payments, on concerns about growing Commonwealth government debt. The EIAC then only came about as a concession to gain Senator David Pocock’s support for the Secure Jobs Better Pay Act 2022.

Labor’s meme of “inheriting a trillion dollar debt that will take generations to pay off” has echoed the Coalition’s 2013 so-called “budget emergency”, also used to blame the preceding government. The nation’s allegedly dire fiscal position was cited by Bill Shorten as justification for not adopting the EIAC’s key recommendations: ‘We can only do what is responsible and sustainable and unfortunately the budget we inherited from the previous government is heaving with a trillion dollars of Liberal debt, so [we] can’t do everything.’

The strategy of deflecting accountability for policy choices on grounds of fiscal constraint has become less credible, given the robust post-pandemic economic recovery and the boom in commodity prices – all of which has generated large improvements in the Commonwealth government’s fiscal position. As illustrated in Figure 1, the government’s underlying cash deficit for the current financial year (2022-23), once expected to be $100 billion, has shrunk dramatically.

Sources: Australian Government, Budget Papers, Monthly Financial Statements. Author’s calculations.

Indeed, the Commonwealth Government’s latest Monthly Financial Statements show that it is on track to post a very small deficit, or even a surplus, for the 2022-23 financial year. As of March 2023 the underlying cash balance (UCB) had improved by $23.3 billion over the estimates in the October 2022-23 Budget. If the year-to-date deficit changes little in the last quarter, and with higher GDP than previously estimated, then the UCB in 2022-23 would come in at a diminutive -0.5% of GDP. That’s insignificant by any meaningful economic standard.

Further upside is possible. If the average monthly improvement from November 2022 to March 2023 continues in the last quarter of the financial year, the UCB in 2022-23 would be a surplus of $2.8 billion.

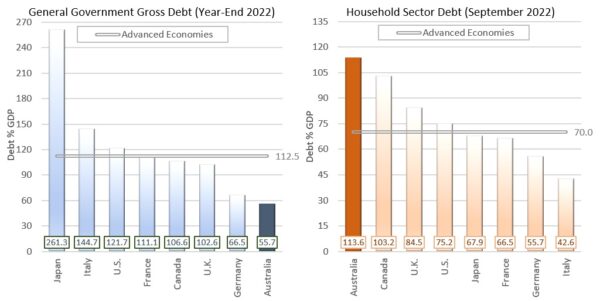

Australia’s public debt load – also measured appropriately as a proportion of GDP (rather than in big scary ‘trillion dollar’ terms) is also modest when compared to the nation’s peers and to its own historical record. Our general government debt (including state governments) is lower than any G7 economy, and half the size of the average for advanced economies. The same cannot be said, however, for Australian households: their debt is higher than any G7 economy, and ranks second (behind only Switzerland) among all industrial countries (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Government and Household Debt

Sources: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Database. Bank for International Settlements, Credit to the Non-Financial Sector.

Having switched from “opposition mode” into “governance mode,” it makes sense for Labor to start to talk up the nation’s public finances. Such a narrative would be plausible given that Australia’s fiscal position is robust and sustainable: now and into the foreseeable future. That is the current assessment of the International Monetary Fund in its latest Article IV Consultation, amongst others.

The prospect for further substantial improvement in the UCB over the forecasts – and perhaps even a surplus – should raise expectations about what the government can do to ease cost-of-living pressures. Arguably, however, a liveable unemployment benefit should be prioritised regardless of the economic and fiscal outlook.

The EIAC’s Jobseeker proposal is estimated to cost $24 billion over four years. Implementing all of the EIAC’s other recommendations brings the cost to $36 billion. The annual cost of the full package would amount, respectively, to just 0.3% of GDP in the next financial year. Such expenditures, while having a diminutive impact on the Commonwealth Government’s fiscal position, would literally transform the lives of the unemployed.

When all is said and done whether a nation should have a liveable unemployment benefit is a question of principles. There is an obvious option for Labor to allay its worries about the budgetary or inflationary pressures of a liveable Jobseeker payment: namely, jettison the 2024-25 Stage 3 tax cuts, that are estimated to cost $300 billion over the first nine years. Tax cuts that mainly benefit high-income earners make no sense in an economic landscape where over 90% of the pre-tax income gains from growth in national income have in recent experience gone to the highest-income 10% of households.

The reluctance of the government to discard or redesign the Stage 3 tax cuts is attributed by some to the Labor Party’s pre-election commitments. It remains that the tick boxes for good governance do not include steadfast adherence to suboptimal policy positions. Overseeing regressive tax cuts, while being unwilling to meaningfully improve the lot of the least well-off, has those principles back-to-front.

Dr Brett Fiebiger is a post-Keynesian economist. His research focuses on macroeconomic policy, growth theory and income distribution.

You might also like

Special Issue of Journal Marks Halfway Point of First Albanese Government

The Journal of Australian Political Economy, a peer-reviewed journal based at the University of Sydney, has today published a special issue evaluating the record of the Albanese government during the first half of its term in office.

The Stage 3 tax cuts will make our bad tax system worse

Australia has one of the weakest tax systems for redistribution among industrial nations, and as Dr Jim Stanford writes, the Stage 3 tax cuts will make it worse.

Fixing the work and care crisis means tackling insecure and unpredictable work

The Fair Work Commission is examining how to reduce insecurity and unpredictability in part-time and casual work to help employees better balance work and care. The Commission is reviewing modern awards that set out terms and conditions of employment for many working Australians to consider how workplace relations settings in awards impact on work and