Economics 101 for the ABCC

The Australian Building and Construction Commission’s decision to press charges against 54 steelworkers for attending a political rally, with potential fines of up to $42,000 per person, is abhorrent on any level. No worker should face this kind of intimidation for participating in peaceful protest.

But why is the ABCC, established to police construction workers and their unions, now going after steelworkers? It claims that since the factory they work at sells steel to construction sites, it is in effect part of the construction industry. But that claim, if taken seriously, means that the whole economy – and all workers – are subject to the ABCC’s crusade.

In this commentary, Jim Stanford explains the basic economics of supply chains to the autocrats at the ABCC.

Economics 101 for the ABCC

by Jim Stanford

Democratic-minded people of any political stripe were shocked by the announcement last week that the Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC) will take legal action against individual steelworkers who participated in a union protest march last October. The ABCC was reestablished by the Coalition government in 2016 to supposedly uphold the rule of law in construction. But almost all of its actions are taken against unions, it mostly ignores employers. It was obviously created as part of a broader government effort to vilify, harass, and hamstring trade unions.

Now the ABCC is pressing charges against 53 workers at Liberty OneSteel (and 1 union organiser) who missed work to attend a union-organised protest march in Melbourne – where they joined 150,000 other demonstrators. The Commission argues the workers’ participation constituted an unauthorised “strike,” and hence they should be punished far more severely than if they had simply missed a day’s work (say, to go fishing). They now face personal fines of up to $42,000 each: if all 54 are convicted and receive the maximum penalty, the fines would total over $2.25 million.

This intimidation and repression against peaceful political protest is both abhorrent and frightening. In a normal democratic country, this sort of repression would be dismissed in the courts as a blatant violation of democratic rights – and morally rejected by civil society as a step toward totalitarianism. It is only because of Australia’s unusual, even bizarre history of top-down state policing of industrial relations that this police-state activity is somehow “normalised.”

One of the most shocking aspects of the ABCC’s crusade, however, is that it isn’t even directed at the construction industry: the targeted individuals all work at a steel factory. The Commission argues that since some of the steel produced by OneSteel is used in building construction, the factory is considered part of the construction sector (as per the terms of the Building and Construction Industry Improvement (BCII) Act).

That argument, if taken seriously, would grant the ABCC power to police workers and their political activity throughout the entire Australian economy. It is a matter of simple economics that any industry in the economy purchases inputs (both goods and services) from dozens of other industries. For the minions at the ABCC who may have never studied economics, this is called a “supply chain.” And thanks to technology, outsourcing, and globalisation, supply chains are longer and more complex than ever.

In fact, if the entire construction supply chain is considered part of “construction,” then essentially the whole economy is construction. Because virtually every industry in the country sells something to construction companies.

To see this, check out the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ magnificent annual “input-output table.” It’s a number-cruncher’s dream: a gigantic matrix that describes the cross-cutting supply chains that feed into every industry. The ABCC might wish to review the latest edition before getting too carried away with its hunt for subversives in every closet.

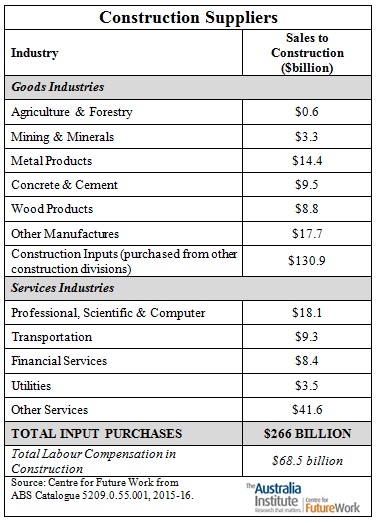

The ABS table includes 113 different industries. Of those, fully 109 sell something to the construction industry. This includes everything from raw materials to sophisticated manufactures, from scientific laboratories to catering. The table below lists a few of the biggest construction suppliers – both goods and services. But virtually no part of the national economy is not connected somehow to construction.

In total, construction firms purchase over one-quarter of a trillion dollars’ worth of supplies and services from those 109 industries (including purchases from other divisions of construction). In fact, the input purchases of the construction industry are four times bigger than the wages and salaries paid to construction workers – revealing again that the ABCC’s obsession with policing construction labour is mightily misplaced.

Here are some of the more interesting sectors which report sales to the construction industry in the ABS tables:

- Fishing and hunting ($70 million): Perhaps for trophies of big game to hang over the fireplace mantles of luxury homes?

- Bakery products ($50 million): Donuts and pies, ‘nuff said.

- Beer manufacturing ($4 million): This seems at first to be a gross underestimation. However, keep in mind that input-output tables do not include goods and services consumed by construction workers on their own time (in which case, this figure would surely measure in the billions!). Rather, it only includes purchases (tax deductible, of course) made by the companies. You can guess who drank the beer.

- Veterinary medicines ($7 million): Must be for the nasty pit bulls at construction sites.

- Gambling ($59 million): Given Australia’s speculative property bubble, it’s not a stretch to consider the whole housing industry to be a form of “gambling”!

- Public order and safety ($769 million): That’s a biggie: security guards, CCTV cameras, and safety supplies. Conceivably the inflated salaries of the ABCC executives might even show up here: since they act in essence like a state police force.

Of the 113 industries tracked by the input-output tables, only 4 do not report any sales to the construction sector. But even those sectors probably have some connection to the builders – perhaps once or twice removed:

- Aquaculture: Construction purchasers buy from the fishing and hunting sector, but not from aquaculture. They must think wild salmon tastes better.

- Library and other information services: Contrary to classist stereotypes, construction workers do indeed read books.

- Primary and secondary education: The industry spends a lot on vocational and tertiary education; but school-level training isn’t counted (perhaps because it was completed before construction workers started their jobs).

- Residential care and social assistance: This is certainly a necessary input for many construction workers – but only after they retire, are injured, or made redundant, and hence have left the industry.

In short, basic economics confirms that the construction industry’s supply chains stretch into virtually every nook and cranny of the whole economy. If the overzealous autocrats at the ABCC are serious that their dominion extends to anyone who supplies construction, then their dominion extends to all of us.

And that is an important, if unintended, lesson. If we allow this outrageous attack on the fundamental rights of assembly and expression of construction workers to proceed, then we are all ultimately vulnerable to the same repression. An injury to one really is an injury to all.

You might also like

Want to lift workers’ productivity? Let’s start with their bosses

Business representatives sit down today with government and others to talk about productivity. Who, according to those business representatives, will need to change the way they do things?

Centre For Future Work to evolve into standalone entity

The Centre for Future Work was established by the Australia Institute in 2016 to conduct and publish progressive economic research on work, employment, and labour markets. Supported by the Australian Union movement, the centre produced cutting edge research and led the national conversation on economic issues facing working people: including the future of jobs, wages

Feeling hopeless? You’re not alone. The untold story behind Australia’s plummeting standard of living

A new report on Australia’s standard of living has found that low real wages, underfunded public services and skyrocketing prices have left many families experiencing hardship and hopelessness.