Job Creation Record Contradicts Tax-Cut Ideology

Share

The Australian Bureau of Statistics released its detailed biennial survey of employment arrangements this week (Catalogue 6306.0, “Employee Earnings and Hours“). Once every two years, it takes a deeper dive into various aspects of work life.

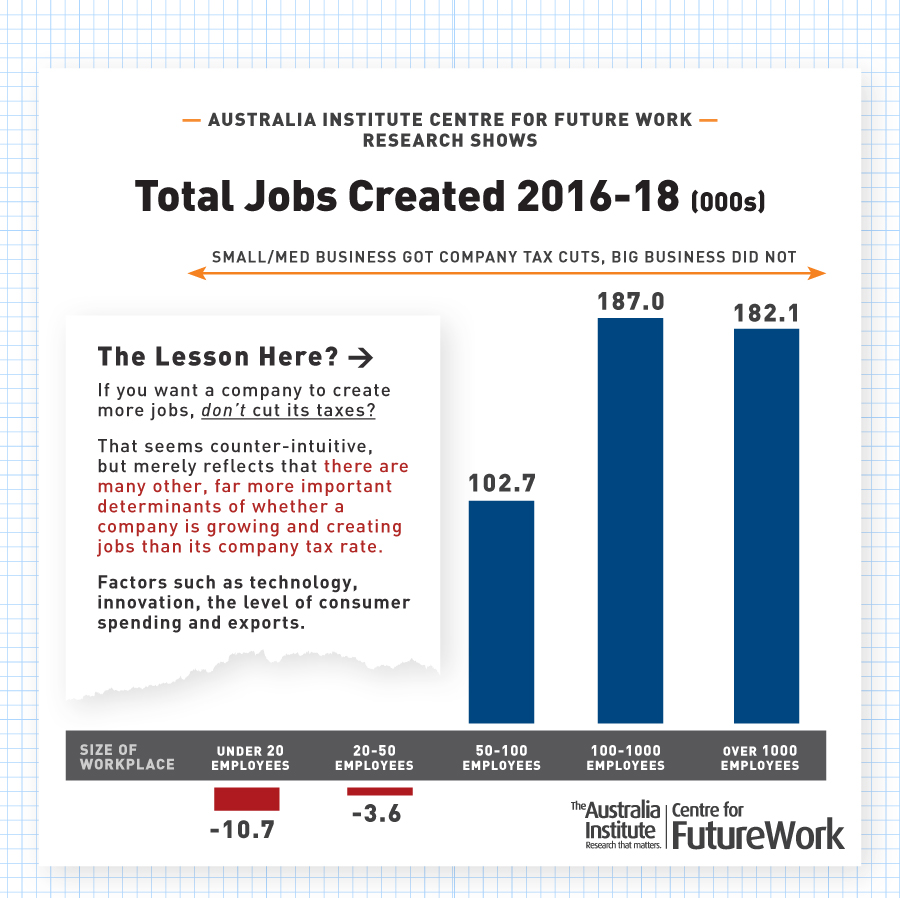

Buried deep in the dozens of statistical tables was a very surprising breakdown of employment by size of workplace. It turns out, surprisingly, that Australia’s biggest workplaces (both private firms and public-sector agencies) have been the leaders of job-creation over the last two years.

This runs against the common refrain that small business is the “engine of growth.” In fact, workplaces with less than 50 employees actually shed employees (14,000 in total) since 2016. Curiously, it was only smaller businesses that received the much-vaunted reduction in company tax (from 30 to 27.5 per cent), also beginning in 2016.

The tax rate for small and medium-sized businesses began to fall in 2016, first for the smallest firms (with turnover under $2 million), and then for firms with up to $50 million revenue. The tax is not tied to the number of employees in a business, but the vast majority of firms which have received the tax cut have less than 50 employees. Yet that is the group that has reduced its workforce since the tax cuts began to be phased in.

In contrast, very large workplaces (with over 1000 employees) added 182,000 new jobs over the two years. Workplaces with between 100 and 1000 employees added 187,000. Very few of those workplaces would have received the reduction in company taxes (since most would exceed the $50 million annual revenue threshold).

Workplaces between 50 and 100 employees created a net total of 103,000 new jobs between 2016 and 2018. Some of those firms would have received the tax cut, and some not — depending on the nature of the business and the amount of total turnover generated per employee.

The data on job-creation by firm size is detailed on Table 13 of Data Cube 1, in the “Downloads” section of the ABS report. The data refers to waged employees, not including owner-managers of businesses.

The share of small businesses (under 50 employees) in total employment declined by two percentage points — since they were reducing their workforces, while larger companies were growing. Small businesses (under 50 employees) now account for 34 per cent of all employees, compared to 36 percent in 2016.

Why would large companies that didn’t get a tax cut create new jobs faster than companies which did benefit from the Coalition tax cuts? (The small business tax cuts are estimated to reduce federal revenues by $29.8 billion over the first decade.) Simple: there are dozens of different factors which determine whether a company is profitable or not, and whether it chooses to grow. Tax rates are just one of those variables. Others include:

- Growth in consumer demand.

- The company’s investments in product quality, innovation, and design.

- Production costs.

- Interest rates and financing costs.

- Business confidence and expectations.

- Management capacity.

- International competition.

Trends in all these other factors can easily overwhelm the marginal impact of lower tax rates. Small business sales in particular have been held back by stagnant wages among Australian workers. Even companies which experience higher profits due to lower tax rates may choose to simply accumulate those profits, or pay them out to shareholders in dividends and share buy-backs (instead of expanding payrolls). Empirical evidence shows this has been the dominant impact of U.S. business tax cuts implemented by Donald Trump.

Changes in tax rates can even have offsetting effects which undermine business conditions and hence reduce job-creation: if the revenue lost to tax cuts results in corresponding reductions in government program spending or infrastructure investments (as seems likely), then overall business conditions might be weakened, not strengthened.

The reduction in employment by the businesses which most benefited from the expensive business tax cuts over the past two years should lead policy-makers of all persuasions to reconsider the argument that this is an effective way to stimulate growth and job-creation. However, in October the government announced it wanted to accelerate the next stages of the small business tax cuts — taking the rate down to 25 per cent five years faster than originally planned.

So far, the policy is akin to shooting oneself in the foot. Instead of reloading the gun to do it again even sooner, perhaps this is a good time to reconsider whether the strategy makes any sense at all.

You might also like

Commonwealth Budget 2025-2026: Our analysis

The Centre for Future Work’s research team has analysed the Commonwealth Government’s budget, focusing on key areas for workers, working lives, and labour markets. As expected with a Federal election looming, the budget is not a horror one of austerity. However, the 2025-2026 budget is characterised by the absence of any significant initiatives. There is

Want to lift workers’ productivity? Let’s start with their bosses

Business representatives sit down today with government and others to talk about productivity. Who, according to those business representatives, will need to change the way they do things?

Dutton’s nuclear push will cost renewable jobs

Dutton’s nuclear push will cost renewable jobs As Australia’s federal election campaign has finally begun, opposition leader Peter Dutton’s proposal to spend hundreds of billions in public money to build seven nuclear power plants across the country has been carefully scrutinized. The technological unfeasibility, staggering cost, and scant detail of the Coalition’s nuclear proposal have