Australia has a proud tradition of impolite, inconvenient protest for worthy causes.

Indeed, Australia Institute research finds most Australians support federal legislation to protect the right to protest and maintain that peaceful protest has a role to play in Australia’s democracy.

The rhetoric of Australian politicians, by contrast, feels increasingly hostile to protesters, even to peaceful protesters.

NSW Police Minister Yasmine Catley said: “I don’t want to see protests on our street at all, from anybody. I don’t think anybody really does.”

South Australian Labor Premier Peter Malinauskas workshopped anti-protest laws on talkback radio before rushing them through the lower house just a day later.

Over the last five years, most states have introduced anti-protest laws. Protestors can be charged much higher fines for expressing their views in the open than lobbyists are charged to express their views privately in exclusive dinners with government ministers.

But non-violent protests, including disruptive and impolite protests, are a key part of the Australian tradition.

Whether it is the fight for LGBT+ rights, women’s suffrage, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sovereignty or better working conditions, Australian protesters have won change through a willingness to disrupt, to offend and to make themselves too inconvenient to ignore.

The eight disruptive but very worthy protests outlined below are examples that cover a range of issues and protest strategies, among the many that could have been highlighted.

Women’s suffrage and feminist protests

Australian women have protested against unequal treatment and sexism for centuries – including by breaking parliamentary rules.

In 1898, two or three hundred women “invaded” the Victorian Legislative Council club-room to “pressure members to pass a women’s suffrage bill”.

By 1902, white women had won suffrage – both equal voting rights and the right to stand for election to the federal Parliament.

Women’s Liberation protesters in the 1960s and 70s also caused disruption. In 1965, academic Merle Thornton and friend Rosalie Bognor locked themselves to the bar of the Regatta Hotel in Toowong, which by Queensland law was barred from serving women from the same bar as men.

Merle and Rosalie received bomb threats and were subject to police surveillance and wire taps, and The Courier-Mail encouraged harassment by publishing their addresses. Despite that, the discriminatory law was repealed and Merle’s later advocacy would encourage the repeal of the law that banned married women from working as public servants.

Source: University of Queensland

Jimmy Clements and John Noble at the opening of Parliament House

Not one Indigenous Australian was invited to the opening of the original Parliament House in 1927.

Two Wiradjuri elders, Jimmy Clements and John Noble, walked 93 kilometres from southern New South Wales to talk about injustices at the “reserve” that they lived on – including being forced to work without pay and children being taken away.

The police tried to move Clements on, but the crowd “rallied to his side”.

Similarly, when Queen Elizabeth II opened new Parliament House in 1988, Aboriginal people and their supporters made a “noisy” protest.

Democrats founder Senator Don Chipp recognised it as a wonderful thing:

In how many other countries on this planet would such a hostile open exhibition of dissent be allowed to proceed in full view of the reigning monarch? In a rather strange way, this outside phenomenon seemed to give real meaning to the many references being made to democracy in the speeches being delivered inside.

Source: National Archives of Australia, ID 3050026

Dockworkers block iron exports to imperialist Japan during World War 2

In 1938 and 1939, Port Kembla dockworkers refused to load pig iron that was going to supply the Japanese military effort during its invasion of China. By this time, the Imperial Japanese Army had already committed mass murder of Chinese civilians and prisoners of war.

Future Liberal Prime Minister Robert Menzies, who called the strike “a provocative act against a friendly power”, was nicknamed “Pig-Iron Bob” over his handling of the strikers.

But the Chinese–Australian community were grateful, sending food from Sydney markets to support striking workers.

Today, a monument commemorates the Port Kembla strikers.

Source: Fairfax Photo Library

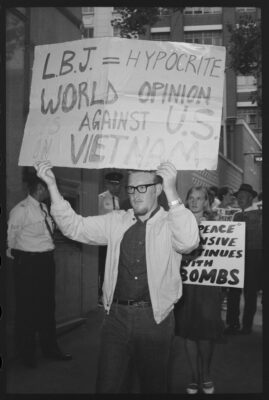

Vietnam War protests

By 1965, a broad coalition of Australians were protesting the Vietnam War – and conscription. They included conscientious objectors, mothers’ groups, students, trade unionists and pensioners.

As Sean Scalmer writes in Dissent Events, young men who had been conscripted burned their draft cards in Belmore Park in early 1966, with one saying: “This is a political gimmick, and I refuse to go to Vietnam”. The Army had thought to out-manoeuvre protesters by moving conscripts away a day earlier, but the self-declared “gimmick” secured front-page newspaper coverage.

Commentators mocked the protesters for their youth and claimed they were only doing it for attention, to “get one’s name into the paper”. But the protesters saw it as a “sincere, if disruptive, display”. Even Labor leader Arthur Calwell led a protest march against “visiting South Vietnamese dictator Marshall Ky”.

Protesters chanting “Hey, hey, LBJ: How many kids did you kill today?” interrupted US President Lyndon B Johnson’s speech. The instinct of the establishment was for violence: when protesters blocked Johnson’s motorcade, NSW Liberal Premier Robin Askin reportedly said: “Ride over the bastards.”

Source: Creative Commons Attribution licence, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales and Courtesy SEARCH Foundation

Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras

In 1978, gay and lesbian people in Australia organised a Mardi Gras to mark the ninth anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in New York. At the time, sex between men was a crime in New South Wales, and it was legal to sack someone for being gay.

When the street parade continued beyond where it had a permit for, the police made their first arrest. The parade became a protest, with attendees chanting: “Stop police attacks on gays, women and blacks!”

Protestor Peter Murphy was taken to an isolated area and bashed by police officers. Fifty-three gay and lesbian activists were charged under the Summary Offences Act. The Sydney Morning Herald published the names, addresses and occupations of all those arrested, an invitation to homophobic vilification which cost some protesters their jobs.

Premier and Police Minister Neville Wran defended the police, but over the next few months, rallies pressured police to drop the charges. The Summary Offences Act was repealed and in 1982 it became illegal in NSW to discriminate on the basis of sexuality. By 1984, homosexuality was decriminalised.

Mardi Gras has been held ever since.

In 2008, “78ers” marked the 30th anniversary of the Mardi Gras. AAP: 20080301000079842168

The anti-apartheid movement

Anti-apartheid activists disrupted the South African rugby team’s 1971 tour of Australia. Protesters “blew whistles, held up placards, and ran onto the field if possible” to interrupt the Springboks’ matches.

Future Labor politician Meredith Burgmann said: “Coming between these blokes and their sport was the most dangerous thing I ever did”.

Trade unionists embargoed South African ships and hotel workers in the Hospitality Union “made life difficult and uncomfortable in hotels” for the racially-selected rugby team.

The protests were initially unpopular, with many Australians holding the view that “sports should be separate from politics”. However, over the course of the tour, attitudes changed.

Sir Donald Bradman cancelled the 1972 cricket tour of South Africa, saying “We will not play them [South Africa] until they choose a team on a non-racist basis”.

The Whitlam Labor Government declared that “racially selected sporting teams from South Africa would not be allowed to enter, or transit through Australia”. This ban stayed in place until the end of apartheid in 1994.

Franklin blockade

In the 1980s, the Tasmanian Labor Government aimed to build a hydro-electric dam on the Gordon River, which would have flooded parts of the Franklin River.

The Tasmanian Wilderness Society’s 1982 blockade disrupted construction of the dam. Protesters were “subjected to counter-protests and retaliation from their opponents”.

The blockade lasted around three months and led to over 1,200 arrests. The cause gained momentum when future Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke campaigned on a promise to stop the dam going ahead if elected. Hawke’s election win secured federal legislation protecting the Franklin River as a conservation site.

Aboriginal Tent Embassy

The Aboriginal Tent Embassy is a permanent protest established on 26 January 1972 in response to the McMahon Liberal Government’s attempts to restrict Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land rights. Then Labor Opposition Leader Gough Whitlam visited the site to discuss the embassy’s demands.

The embassy “faced a large contingent of politicians and members of the public who believed the protesters were trespassing and the tents were an eyesore.” The government introduced laws to shut down the camp, but hundreds and then thousands of protesters defended the embassy. The embassy was forced to move, but in 1992 returned to the original site.

Over more than half a century, the embassy has stood up for land rights, First Nations sovereignty and self-determination.

Source: Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike, Australian Information Service, Canberra

These are just eight examples of brave, disruptive protests. There are many more that could have been featured. After all, it is the 20th anniversary of the Howard Government’s WorkChoices. The “Your Rights at Work” campaign involved community mobilisation and protest on a grand scale – by some accounts, the biggest demonstrations in Melbourne since the Vietnam War. Other examples would be the union campaign for an eight-hour work day in the 19th Century and the Wave Hill walk-off in the 1960s that brought Aboriginal land rights to the fore.

Few Australians now would call anti-Vietnam War protests indulgent or attention-seeking, or say that enjoying a rugby match is more important than fighting the apartheid regime in South Africa. The Aboriginal Tent Embassy is now a key part of Australian heritage and the movement for Indigenous rights, though it was treated as trespass when it began. The first Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras was met with violence by police; now NSW Police is keen to march in that same parade.

Disruptive protest is an Australian tradition, and one that most Australians want to see protected.

You might also like

Closing Loopholes Protections, Including Right to Disconnect, Come Into Effect 26 August

New labour rights coming into effect on 26 August, including the ‘Right to Disconnect’.

Analysis: Will 2025 be a good or bad year for women workers in Australia?

In 2024 we saw some welcome developments for working women, led by government reforms. Benefits from these changes will continue in 2025. However, this year, technological, social and political changes may challenge working women’s economic security and threaten progress towards gender equality at work Here’s our list of five areas we think will impact on

The 9 to 5 is back! Time to put the phone on silent

If you’ve ever flicked off an email before bed, texted your boss out of hours, or received an ‘urgent’ work call after clocking off, you’ll be glad to hear some respite is just around the corner. A new right to disconnect from work, for employees in businesses with 15 or more staff, comes into force